1998 saw the birth of Shinichiro Watanabe’s main directorial debut Cowboy Bebop. Having started off as a household episode director and storyboard artist for various Sunrise shows since the mid-80s, Watanabe first gained recognition in 1994 as the co-director for the largely celebrated Macross Plus OVA, a job which he had received after encountering mecha designer and Macross franchise creator Shoji Kawamori during the production of the Gundam OVA 0083: Stardust Memory from 1991. This then resulted in Sunrise giving him the opportunity for his own first original project, which in 1998 came in the form of Cowboy Bebop. While Watanabe’s only given instruction for the series was that he could create whatever he wanted as long as it included a spaceship – due to Sunrise’s sponsorship with the Bandai company’s toy division – it however quickly became apparent that his intentions did not match that of Bandai’s. Thus, the company dropped the project, leaving it in development hell until their sister company Bandai Visual picked it up again. This ultimately resulted in Watanabe gaining complete free rein, given that he didn’t have to worry about merchandise sells anymore; a free rein that he made sure to take advantage of to its fullest. With a significantly high production value for its time, the series saw a number of highly skilled staff members coming together in both writing, directing, animation, design and music. Not least did the staff list include several people from the previous Macross Plus team, such as Kawamori himself who provided scriptwriting for episode 18 and overall design assistance, and also scriptwriter and series composer Keiko Nobumoto, as well as music composer Yoko Kanno. The show also notably saw the debut of Dai Sato, who worked as a set designer alongside Kawamori as well as scriptwriter for three episodes.

Conceptually, Watanabe had originally thought for Cowboy Bebop to be a movie, which subsequently made him treat each individual episode as such during production. He has also expressed how the show to a large degree is a tribute to American movies and TV-series that he saw airing in Japan during the 70s and 80s. These two main factors are arguably the most relevant in relation to the basic foundation of the show, as they not only make it a collection of self-contained stories, but ones that each have their own unique flavor, embodying a variety of styles from across the cinematic spectrum. The next episode that you turn on could be anything from an elegant film noir, to a philosophically intricate cyberpunk, to a gruesome gangster drama, to a cheesy exploitation b-movie, to a wacky comedy. Some episodes are even direct pastiches of specific movies, like in the case with the episode Toys in the Attic being a homage/parody of Ridley Scott’s 1979 sci-fi horror classic Alien. But while Cowboy Bebop embodies a number of different styles during its 26 episode runtime, one genre that is strongly prominent throughout the series as a whole is western. The depiction of the harsh, lawless life of the fictionalized and romanticized reimagining of the American frontier known as the Wild West is in Cowboy Bebop adapted as principally as in its basic premise; a group of bounty hunters, or ”cowboys”, who travel through space in search for wanted criminals. Beyond that, it also borrows a lot of the same tropes as found in western fiction, such as its typically gun-oriented action, its many western saloon bars, and its very desolate atmosphere that is specifically characteristic of spaghetti westerns.

But it doesn’t stop there, because Bebop isn’t just a western, but a space western; a sub-categorial blend between western and science fiction. This is a genre that, to a more or less extent, has existed since the 1930s when its two halves often would clash together in early pulp magazines. Since then and until today, it has taken a lot of different forms in both literature, comic books, movies and TV-series, either as a subtle compartment to an otherwise general sci-fi setting, or as a fully fledged embracement with cowboy hats, revolvers, horse riding and so on. The genre saw a peculiar trend within anime during the 90s, particularly in the form of three titles; Trigun, Outlaw Star and Cowboy Bebop, all of which were released in 1998. While its two contemporaries each have their own interesting variations on the space western genre, Bebop is among them a bit unique in that its approach is at the same time very literal and very grounded, focusing on the Wild West’s colonialist aspect in a notably realistic manner.

As a historical era, the American frontier is a typical example of a colonial society where national and political establishment was in its developmental stage, meaning that law and order wasn’t in its most stable condition (which was essentially what the western genre amplified by depicting a borderline anarchist environment). This sort of postcolonial instability is also what ultimately defines the society of Cowboy Bebop. The show is set in the year 2071, sixty years after the Earth has become uninhabited due to a hyperspace gateway accident, which had forced humanity to colonize the moons and rock planets throughout the solar system. Because of this radical change, humanity as a civilization has become highly unstable with a crime rate that’s higher than ever, which has made the only existing resemblance of a law enforcement, the Inter Solar System Police, recruit bounty hunters. Here we can see how at one level, this future era is, just like the Wild West, in a premature stage of post-colonization where universal settlement and governmental control hasn’t been fully established yet, and therefore has a mildly anarchistic social order. At yet another level, this society is also in a state of post-trauma, trying to recover from the catastrophic incident that lead to this point. The desolate atmosphere is there for a reason (beyond being reminiscent of spaghetti westerns), to express the wound that this trauma has created. Humanity is in as much a process of settlement as in a healing process.

However, anarchism and desolation wasn’t the only thing that this incident and its following colonization lead to, but also a blend of cultures. As nations one by one went under, so did their borders, which led humanity’s many cultures come together into a huge societal melting pot. Bebop is thus filled to the brim with influences and appearances of cultures from all over the world, something that is apparent not least in its wide variety of ethnicities (which Watanabe himself expressively put high emphasis on), but also in its various locations. We see a Mars being modeled after Hong Kong, a Venus after 19th century Istanbul, a Ganymede after Marseille, and an asteroid after Tijuana.

Worth noting is also how each of these world cities have some sort of attribute to them that’s fittingly relatable to the show’s multicultural setting. Hong Kong has a long and complicated history of cultural ambiguity, having been under (mostly British) colonial ownership until as late as 1997; Istanbul is transcontinentally located at the border between Europe and Asia; Marseille was the main trade port for the French Empire during its time and historically the most important trade center in its region; and Tijuana is similarly today one of the biggest metropolitan areas in Mexico and a major growing cultural centre, being the most frequently visited border city in the world. Cultural diversity is undeniably something that is extremely prominent throughout this entire society, not just between its different cities but within them as well.

This diversity isn’t just expressed through the show’s visual presentation, but also through its use of music. The major role that the musical art form has in this show becomes apparent as early as in the title, who’s latter half references to a sub genre within jazz music. The episodes themselves are furthermore called “sessions”, suggesting that they are as much told stories as improvisatory and unpredictable jam sessions, which is quite fitting considering the stylistic nuances in and between each episode. Even the names of the episodes are going along with the music theme, by either referring to a certain genre – “Asteroid Blues”, “Waltz for Venus”, “Mushroom Samba” – or a specific song – “Sympathy for the Devil”, “Toys in the Attic”, “Bohemian Rhapsody”, “My Funny Valentine”.

Although naturally, the music emphasis is nowhere as prominent as in the score itself, which strongly goes in the same vein of cultural and stylistic diversity as the rest of the show’s content. Yoko Kanno is a composer generally known for blending varieties of musical styles in her compositions, but even among her many other fantastic works, Bebop is a special case. It is a score that quite literally has a life of its own, not just in the sense that it musically exceeds its purpose as background music, but also from a mere production standpoint. As Watanabe explained at a Q&A, the development of the score wasn’t done through mere requests, but was a mutually collaborative process that developed alongside the show itself, a process that he described as a “game of catch”. Kanno would get inspired on her own and come up with songs that Watanabe had never asked for, which he then would draw inspiration from and add new scenes to the show. These scenes would then further inspire Kanno, leading to even more music, and so on and so forth. The score was thus not created solely for the show, but with the show.

While the main focus of Cowboy Bebop‘s music is undoubtedly jazz – a genre which in itself is extremely broad, and pretty much lives and breathes stylistic mixing and experimentation – it also embodies a ton of other genres such as rock, blues, country, Latin and middle-eastern music, EDM and opera. This blending doesn’t just appear from song to song, but within specific songs as well. The Blade Runner-esque synth and saxophone combination accompanied by a Native American choir of Space Lion, the funky bass line and samba rhythm of Mushroom Hunting, the jazzy saxophone and arabic harmonies of Bindy, and the dub reggae vibes and horn section of Pot City, are all strong examples of this.

One of the most contributing factors to this is arguably the wide variety of musicians from all over the world involved in the making of this music. As the main performing ensemble for the score, Kanno put together a jazz big band called Seatbelts, which included an extensive amount of musicians from both Japan, New York and Paris. A number of outside collaborators also contributed to the score, including guest singers such as Steve Conte, Mai Yamane, Jerzy Knetig, Raj Ramayya and Ilaria Graziano, musicians such as Hassan Bohmide and Pierre Bensusan, as well as legendary recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder. With its vast amount of names stemming from places all around the globe, the collection of musicians behind this score is indeed a cultural melting pot in itself.

Summary-wise, we can see how the world surrounding Cowboy Bebop is brimming with cultural nuances in every aspect; from its people, to its locations, to its music. But it is also a world whose society is in a broken condition, with desolation, crime and poverty being present around every corner. The almost haunting ambience that is humanity’s post-trauma gives a rather bitter aftertaste to its otherwise wonderfully rich mixture of flavors. And because of the radical colonizing process that this trauma caused, human civilization is currently in an ambivalent phase between two states of belonging; it has cut ties with its original home but not settled down at its new one as a united people. While consisting of an extensive variety of cultural expressions clashing together like never before, it at the same time has no mutually shared Culture. It is a society in inner exile, lacking of any collective identity.

And among all this, we have the series’ four main characters, who are just as much amalgamations of various influences as the world that surrounds them. Alongside the aforementioned American films and TV-series, one of the main inspirations that Watanabe had for the show was Monkey Punch’s classic manga and anime franchise Lupin III, and never is this so apparent as in some of the characters. Spike shares the same body shape and boots as well as gentlemanly persona as the titular character; Jet’s gruff old-man-personality, responsible ”big brother”-relationship with the rest of the ensemble, as well as his beard is similar to that of Daisuke Jigen; Faye shares the seductive charisma, deceptiveness and selfishness of Fujiko Mine; and Vicious has the same appearance and Katana skills as Goemon Ishikawa.

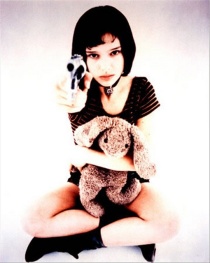

Furthermore, the main inspiration for Spike’s physical appearance was that of famed Japanese actor Yusaku Matsuda – best known for his roles in action films and TV-series during the 70s – and particularly as he appeared in the TV-series Tantei Monogatari. The most striking resemblance between the two would be their large fluffy hairstyles. On top of this, Spike’s outfit consists of a blue leisure suit, a clothing most commonly associated with the 70s American disco culture. He also has a fighting style largely inspired by, if  not entirely adapted from, Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do. Moreover can Faye’s physical appearance – her shorts, underskirt, overcoat and not least hairstyle – be seen as an aged homage to Natalie Portman’s character Mathilda Lando in Luc Besson’s 1994 crime drama thriller Léon. Her personality too is to a large degree a mixture between Mathilda and the aforementioned Fujiko Mine; she’s a sleazy seductress and independent, self-centered woman on the surface, but on the inside she’s an insecure human being with a troubled past, who’s learned to take care of herself the hard way. And finally, Ed carries str

not entirely adapted from, Bruce Lee’s Jeet Kune Do. Moreover can Faye’s physical appearance – her shorts, underskirt, overcoat and not least hairstyle – be seen as an aged homage to Natalie Portman’s character Mathilda Lando in Luc Besson’s 1994 crime drama thriller Léon. Her personality too is to a large degree a mixture between Mathilda and the aforementioned Fujiko Mine; she’s a sleazy seductress and independent, self-centered woman on the surface, but on the inside she’s an insecure human being with a troubled past, who’s learned to take care of herself the hard way. And finally, Ed carries str ikingly similar characteristics to that of Swedish children’s books author Astrid Lindgren’s fictional character Pippi Longstocking. This includes her childish, free-spirited carefreeness, her red hair, and not to mention both their equally ridiculously long full names: ”Pippilotta Viktualia Rullgardina Krusmynta Efraimsdotter Långstrump” and ”Edward Wong Hau Pepelu Tivrusky IV”.

ikingly similar characteristics to that of Swedish children’s books author Astrid Lindgren’s fictional character Pippi Longstocking. This includes her childish, free-spirited carefreeness, her red hair, and not to mention both their equally ridiculously long full names: ”Pippilotta Viktualia Rullgardina Krusmynta Efraimsdotter Långstrump” and ”Edward Wong Hau Pepelu Tivrusky IV”.

What each of these four individuals have in common though is a struggle of trying to find out who they are and where they belong. They all have their respective troubled relationships with their pasts; Faye has a massive debt and suffers from amnesia after a space shuttle accident put her in a 54 years long cryogenic sleep, Ed was at an early age left at an orphanage by her distant father, Jet is an ex-ISSP investigator who quit after losing his arm in a corrupt case, and Spike was once a member of a crime syndicate which he left after a dramatic love triangle. Now they’re all stuck together on a small spaceship traveling through the solar system, searching for bounties that will give them enough money to get through the day, while at the same time trying to find a sense of identity and belonging.

Here we can see how these four characters ultimately mirror the society that surrounds them. Not least are both sides melting pots of various multicultural influences, but they are also (and perhaps most essentially) in equal states of inner exile. With the very troubled pasts that they all carry, these four people are just like human civilization at large stuck in an ambivalence between two states of interior settlement (which is symbolically represented by their always traveling spaceship of a home). Despite all having a lot of character in them, their identities are ultimately lost in these internal struggles and will only be re-found when they make up with their respective pasts. And this is what I’d say Cowboy Bebop boils down to in the end; at the center of this big melting pot of cultures, films, TV-series and music we essentially see people (whether it be our main characters or society in general) trying to find their place in a tumultuous environment; an environment that exists on as much an external as an internal level.

Excellently informative writeup! I loved how your overarching focus was to showcase the ‘melting pot of cultures’ through Bebop’s music and various settings. It made me appreciate Bebop a whole lot more 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you! I’m very glad it did 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I already enjoy the show and freaking loved the music they used. Had a long marathon re-watch last year This sure does put on a pair of different glasses when looking at this show.

I could host a new marathon this year LOL

LikeLiked by 2 people

Haha, well I actually got tempted to do a re-watch myself at the time of my writing. It really gives you a new perspective on a show when you do this type of analysis.

LikeLike

That is very true but over analysing may even ruin the enjoyment. A background on why is great fun, but dissecting an Anime is just a bit going to far.

I would say you got to. It still a show to enjoy much like Lupin has some resemblance.

LikeLike

Oh wow. This is very impressive. I was very young when I first watched Cowboy Bebop. . .just a child actually, so I the plot itself is now blurry in my memories. But now that I think about it, the series did contain a lot of multicultural nuances. I certainly didn’t notice that as a child, but as an adult I have a deeper appreciation of it. Great post. It’s very insightful. Thank you very much for submitting this intelligent post at the Fujinsei Blog Carnival. I hope that you submit another great one at the next carnival next month. Cheers!

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] “Shinichiro Watanabe and the power of creative diversity | Cowboy Bebop: Colonialism, multicul… by MindMischief (blautoothdmand) – an impressive and well-written post discussing multicultural nuances among other things in Cowboy Bebop. A must-read! […]

LikeLike

This is an excellent insight. I never really saw Cowboy Bebop in such a light and this has made want to rewatch the series.

LikeLiked by 1 person

[…] a través de Shinichiro Watanabe and the power of creative diversity | Cowboy Bebop: Colonialism, multiculturalis… […]

LikeLike

Reblogged this on ☀The Honey Tiger☀.

LikeLike